Here comes the part that every severely sleep-deprived parent is waiting for: What can parents do to reduce the number of night wakings of a baby? Researchers have tested the efficacy of several “sleep-training” methods. One could think of several measures to quantify the efficacy of a method, like the delay between bedtime and actual sleep, or the total time spent awake during the night. The main measure of efficacy discussed below is the number of night wakings, because (i) this one was assessed in most studies, and (ii) from my own anecdotical experience, many short wakings are harder on the parents than a single long waking. Note that the numbers of night wakings mentioned throughout this article are those that the parents reported. The baby could possibly have woken up more often and self-soothed without signaling.

The long-term effects, positive or negative, of sleep training methods on outcomes other than sleep (like behavioral problems, chronic stress or quality of attachment) will be discussed in part 4. Here I focus on short-to-mid-term efficacy on infant sleep fragmentation.

I present below the studies where no medication was involved, and where the mean age of the infants was comprised between 6 and 12 months (sleep training is generally not considered appropriate before 6 months). The tested methods include:

• Putting the infant into bed while partially awake

• Extinction, also called “crying it out” or systematic ignoring

• Graduated extinction type I

• Graduated extinction type II, also called gradual extinction, controlled crying, controlled comforting, ferberizing, or progressive delay responding (this is the one we used)

• Extinction with parental presence, also known as “camping out”, parental presence fading, adult fading, or shaping

• Bedtime fading

Put the infant into bed while partially awake, instead of waiting that he or she is fully asleep

The rationale behind this recommendation is that parents contribute inadvertently to night waking when they rock, hold and/or feed their baby to get them to sleep. When this occurs, the infant establishes a learned association between parental presence and falling asleep – a so-called “sleep-onset association”. Consequently, when the infant awakens, he or she desires the same condition (parental presence) in order to fall back asleep (Adair et al. 1992).

To test this hypothesis, Robin Adair, from Boston City Hospital, and her collaborators compared two large groups of infants visiting the Lahey Clinic Medical Center (Burlington, Massachusetts). In the “intervention” group (n=164 infants), parents received written information regarding sleep-onset associations at the 4-month visit, completed a sleep chart prior to the 6-month visit and discussed it with the pediatrician at the 6-month visit. In the control group (n=128 infants), parents did not receive any specific information about sleep-onset associations during those visits. Both groups were compared at the 9-month visit.

Frequent night wakings were almost twice as frequent in the control group (27% of infants) as in the intervention group (14%).

At 9 months, infants in the intervention group woke significantly less frequently (0.36 wakings per night on average) than infants in the control group (0.56 wakings) (Adair et al, 1992). Frequent night wakings, defined here as more than one waking per night, were almost twice as frequent in the control group (27% of infants) as in the intervention group (14%). The intervention information had been presented as a suggestion rather than an imperative, hence the researchers asked the parents whether they were actually present or not when their child fell asleep. Comparatively more parents were not present in the intervention group (79%) than in the control group (67%), thereby suggesting that at least some parents had followed the instructions. Among intervention parents, only 9% of those who had followed the suggestion reported frequent night waking, versus 31% of those who had not followed the suggestion.

There is thus solid empirical support for the advice of putting the infant into bed while partially awake. It is thus a precious advice — perhaps the most precious advice — for parents of very young infants, to help prevent future sleep problems. My own experience tends to confirm this. I followed this advice with my second child almost all the time (almost, because I still wanted to enjoy the magical feeling of having him fall asleep on my shoulder from times to times!), and we did not face the terrible nights we had to endure with his elder sister.

That being said, if your baby is already more than 6 months old and is used to fall asleep in your presence, this advice alone does not tell you how to react when he or she cries because you tried to let him or her fall asleep alone for the first time. When sleep problems are there, what can you do?

Extinction

Also known as: “crying it out”, systematic ignoring

Sorry we’re closed by Joeannenah | Flickr

This is a method that many parents and professionals find really hard to do. The parents put the child to bed at a designated bedtime and then ignore the child until a set time the next morning, unless they suspect illness or danger. In that case, they check the child in silence and with a minimum of light.

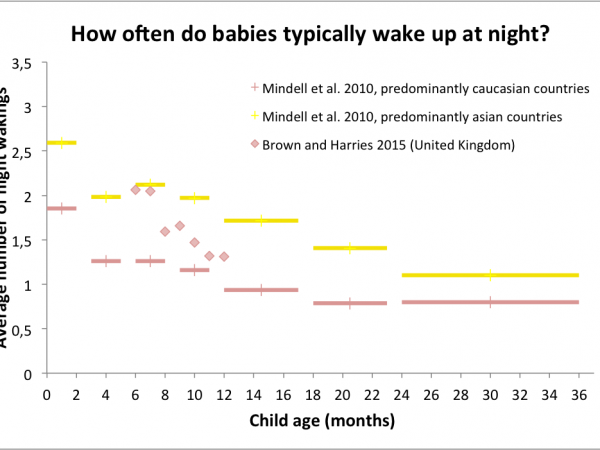

This method has been tested in 1990 on 7 infants, aged 8 to 20 months, by Karyn France and Stephen Hudson, from University of Canterbury (Christchurch, New Zealand). The parents were instructed to use the extinction method for four weeks, unless the child was sick, in which case the intervention was discontinued until symptoms abated. After that, as part of a maintenance program, parents were instructed to check on their child if he or she called, but to leave immediately if there was no acceptable reason, like illness, for the call. Should waking in excess of once or twice a week resume, parents were instructed to return to the initial program. On average, the children of this study woke up 3.31 per night before the intervention (range 1.36 to 5.14). After four weeks of intervention, the average number of night wakings dropped to 0.83 wakings per night (range 0.34 to 1.68) (France and Hudson, 1990). For all children except for Child 3 (for whom the program had been suspended because of illness), these decreases were marked and were maintained at both 3 months (mean=0.45 wakings per night; range 0.00 to 1.23) and 2 years (mean=0.16 wakings per night; range 0.00 to 0.50) after the intervention. Night wakings were not only less frequent, they were also much shorter: 50.3 minutes on average before the intervention, 17.1 minutes after four weeks, 7.1 minutes after three months, and 2.8 minutes after two years (France and Hudson, 1990).

This study thus supports the efficacy of the extinction method. There are, however, several limits to be noted. First, the study used a very small sample and did not use a control group without sleep training. Without such a control group, one cannot rule out that maturation, rather than sleep training, was actually responsible for the improvement of sleep. Second, as noted by Lawton et al. (1991), “anecdotical evidence suggests that many parents have tried to deal with sleep problems by “letting the child cry” and have then been unable to cope with the sustained and intense behavior that ensued”. Several gentler variants of the extinction method have thus been proposed and tested.

Graduated extinction type I

In this first gentler variant of the extinction method, parents respond immediately upon hearing their child but give progressively shorter and shorter periods of attention. To do so, parents first record over two weeks the duration of each parental attend after a night waking. Then they compute the average duration D of an attend. Then they reduce this time by approximately 1/7th each four days, to reach zero by 28 days. A parental attend would thus last:

| Nights | Duration of a parental attend after a night waking |

|---|---|

| 1 to 4 | D minutes |

| 5 to 8 | D*6/7 minutes |

| 9 to 12 | D*5/7 minutes |

| 13 to 16 | D*4/7 minutes |

| 17 to 20 | D*3/7 minutes |

| 21 to 24 | D*2/7 minutes |

| 25 to 28 | D*1/7 minutes |

| 29 and subsequent | 0 minutes |

After those 28 days of graduated extinction, the regular extinction method is applied for at least two weeks, until no further improvement is evident.

This method has been tested in New Zealand by Carolyn Lawton and her collaborators on a small sample of 6 infants, aged 6 to 14 months (Lawton et al. 1991). Immediately after the intervention, only half of the infants showed a clear reduction of their night waking frequency, while the other half showed either a slight reduction or no change. However, two months later (hence roughly four months after the start of the intervention), the average number of wakings per night was comprised between 0 and 1.14 (with a mean of 0.33 over the six infants), and the mean duration of each waking did not exceed 5 minutes for any child.

The end results are thus comparable to those obtained with the regular extinction method, but seem to take more time to be reached. Moreover, although the parents were satisfied with the method, they nonetheless rated it as “somewhat stressful”. If the method is perceived as stressful, there is a risk that parents give up before it produces effects. This risk, combined with the fact that this method is more complicated than regular extinction, led the authors to conclude that “regular extinction is generally to be preferred” (Lawton et al. 1991). Although it would have been interesting to test the method again with a larger sample and with a control group, I could not find another study testing this method, at least not on infants aged 6 to 12 months.

Graduated extinction type II

Also known as: gradual extinction, controlled crying, controlled comforting, ferberizing, progressive delay responding, checking

I am waiting, by George Hodan

This second gentler variant of the extinction method is much more widespread and more studied than the first one. In this method, parents ignore bedtime crying for specified periods. For example (Leeson et al. 1994), once the infant cries, if he or she is not sick and if it is time to sleep, the parents wait for 2 minutes before briefly reassuring the child. The brief check involves comforting the child for a brief period — 15 seconds to one minute — with minimal interaction, without taking the child out of the cot. Then if the crying persists, they wait for 4 minutes to briefly reassure him or her again. The delay is then increased to 6, 8 and 10 minutes. The parent then continues to go in at 10 min intervals. On the rare occasion that the baby is still crying after an hour of controlled crying, the child is picked up, offered a drink of water and calmed down. The controlled crying procedure is then restarted at 2 min. Nighttime feeding, if needed, is done just once early in the night, when the child is not awake and demanding. At 11 pm for example, the sleeping baby is lifted and fed quietly, without fully arousing him or her, and no other night feed is given after this one.

The duration or interval between check-ins with the child can be tailored to the child’s age and temperament, as well as the parents’ judgment of how long they can tolerate the child’s crying. Parents can either wait progressively longer intervals as described above, or employ a fixed schedule (e.g., reassure every 5 minutes).

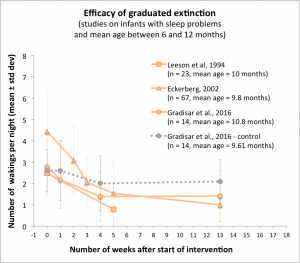

One early test of this method on infants was on a sample of 23 Australian infants aged 8 to 12.5 months. These infants woke up on average 2.48 times per night before the intervention, and only 0.78 times after one month of using the method (Leeson et al. 1994). Marked effects were thus obtained as fast as with the regular extinction method.

Similar results were observed in a slightly larger study of 67 Swedish infants aged 9.8 months on average (Eckerberg, 2002). In this study, the pediatrician Berndt Eckerberg tested a two-step variation of the method, where graduated extinction is done at bedtime only during two weeks, and then both at bedtime and after nocturnal awakenings during the following weeks. A total of 58 of the 67 children already had fewer signalled wakings as a result of evening intervention only. After one month, for the whole sample, the mean number of night wakings per night had dropped from 4.4 to 1.5.

Both studies, however, suffer from a lack of a control group. One cannot exclude that the observed drop in night wakings is merely due to normal maturation, as infants get a bit older during the intervention. Rather than a so-called “within-subject” (before/after) experimental design where everybody is treated, what is needed is a “randomized controlled trial” where subjects are randomly assigned to treatment or control.

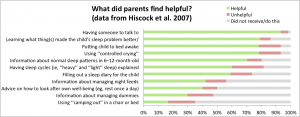

In 2002, Harriet Hiscock and M.Wake, from Royal Children’s Hospital (Melbourne, Australia) carried out a such a randomized controlled trial, on 156 infants, aged 8.75 months on average. The 78 families in the control group merely received a single sheet describing normal sleep patterns in infants, while the 78 other families in the intervention group were given the choice between graduated extinction or extinction with parental presence (see below for a description of this method). Most families, 77% to be precise, chose graduated extinction. Compliance was not perfect but still rather good: 77% of the intervention families used their chosen strategy all the time or most of the time, 13% used it “about half the time,” and 10% “a little of the time”. The statistical analysis was nonetheless performed on the whole sample (such a so-called “intention-to-treat” analysis aims at testing whether a treatment has a visible effect even if not all patients comply with it). Families were free to seek for additional professional help: 6% did so in the intervention group and 21% in the control group. Two months post-intervention, more infant sleep problems had resolved in the intervention group than in the control group (70% versus 47%) and the remaining sleep problems were less severe in the intervention group (Hiscock and Wake, 2002). By four months however, the difference between both groups was no longer significant. It could have been due to families in the intervention group stopping to use the methods, or to families in the control group starting to use a method (found by their own means), or to a natural tendency for sleep problems to improve with time, or a combination of the three.

Intervention mothers had significantly lower postnatal depression scores than control mothers after both 3 months and 5 months of intervention

In 2007, Harriet Hiscock and her collaborators replicated this study on a larger sample of 328 seven-month old infants. 154 families were allocated to control, and 174 families were allocated to intervention, but only 100 families actually took up the intervention, which was on a voluntary basis. Among them, 56% used the sleep strategies ‘‘most’’ to ‘‘almost all of the time’’; only 7% reported no use. Like in 2002, the statistical analysis was nonetheless carried out on the whole initial sample, that is, with n=174 for the intervention group. Families were again free to seek for additional professional help: 8.6% did so in the intervention group and 21.1% in the control group. Three months after the intervention, when the infants were 10 months old, sleep problems were resolved for 44% of intervention and 32% of control families. Two months later, these fractions increased to 61% and 45% respectively. After adjusting for potential confounders (perceived nurse competency, socio-economic status and parents’ educational level, and whether the mother received paid professional help for the infant’s sleep problem), the odds of reporting a sleep problem in the intervention group were 42% lower at 10 months and 50% lower at 12 months compared with the control group. Moreover, while the mean postnatal depression score was identical in both groups of mothers before the intervention, intervention mothers had significantly lower postnatal depression scores than control mothers after both 3 months and 5 months of intervention.

Given that there again, not all intervention families actually did the intervention and control families could seek for help and possibly apply a sleep training method after all, and given the conservative choice made for the statistical analyses, it is remarkable that marked differences are observed between intervention and control. This suggests that using graduated extinction or extinction with parental presence is truly effective in improving the sleep quality of families.

Last year, Michael Gradisar, from Flinders University (Adelaide, Australia), and his collaborators also carried out a randomized controlled trial for two sleep training methods including graduated extinction. The sample was much smaller than in both previous studies, but the experimental design had the advantage to not mix several methods in a single “intervention” group, and to report quantified measures of sleep quality, like the number of night wakings, rather than a yes/no question about the existence of sleep problems. A total of 43 infants, aged 10.8 months on average, were randomized to receive either graduated extinction (n = 14), bedtime fading (n = 15, see below), or merely information about normal sleep patterns (control group, n = 14). The graduated extinction method was used with the following schedule:

| Night | 1st Wait | 2nd Wait | 3rd Wait | Subsequent Waits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2 | 4 | 6 | 6 |

| 2nd | 3 | 5 | 7 | 7 |

| 3rd | 5 | 10 | 15 | 15 |

| 4th | 10 | 15 | 20 | 20 |

| 5th | 15 | 20 | 25 | 25 |

| 6th | 20 | 25 | 30 | 30 |

| 7th | 25 | 30 | 35 | 35 |

After three months, there was a large decline in the number of awakenings for infants in the graduated extinction group, but no changes for infants in the bedtime fading or control groups. This tends to confirm that using graduated extinction is more effective than just waiting. However, this conclusion was based on only 23 infants, as data went missing for several infants in each group.

Extinction with parental presence

Also known as: “camping out”, parental presence fading, adult fading, shaping

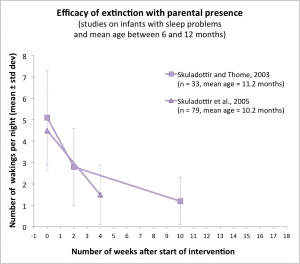

This third gentler variant of the extinction method has the parent remain in a chair or a bed in the child’s room during the extinction procedure, and can incorporate ‘fading out’ where the parent gradually removes him/herself from the bedroom (Galland and Mitchell, 2010). For example, as described in (Skuladottir and Thome, 2003), the parent sits on a chair after the child has been put to bed and does not leave the room until the child is fully asleep. The parent gradually reduces contact with the child over successive nights, from touching to talking to looking away to moving the chair further from the bed.

Once the child has learned to fall asleep without active involvement from the parent, the parent puts the child to bed, leaves the room for a few seconds, returns before the child would start to cry, and stays until the child falls asleep. If the child wakes up during the night, the parent waits for 1 to 3 minutes and then responds in the same manner as for bedtime.

In 1997, Arna Skuladottir and Marga Thome, from Landspitali University Hospital and University of Iceland (Reykjavik, Iceland), tested this protocol with 33 infants, aged 11 months on average, who woke up 5.1 times per night on average (Skuladottir and Thome 2003). In addition to the instructions above, parents were also taught about their role of modulating the environment of the child, their problem of admitting that they themselves needed uninterrupted night sleep, the impact of sleep problems on siblings and family life, the impact of infant crying on parents, the increased risk of child abuse with infants having severe sleep problems, infant individuality, and expectations that can be made about normal sleep at each age. Moreover, they were told to rearrange the child’s sleeping place (for example by preparing a private room for the child), to develop regular day sleep routines and feeding habits, to ensure regular and positive communication, interaction and playtime, and to take some time off for leisure or do anything that could be good for the parents and their relationship.

After ten days of following this advice and using “camping out”, the mean number of night wakings on the 33 infants had dropped from 5.1±2.2 per night to 2.8±1.8 per night. Two months later, it was down to 1.2±1.1 per night.

In 2005, Arna Skuladottir and her collaborators replicated this study on a larger sample of 79 infants, aged 10.2 months on average and waking up 4.5±1.9 per night on average. The protocol was identical to the previous one, except that parents were also instructed to keep the child awake for four hours at least before night sleep if he or she was usually taking two day naps, and for five to six hours if he or she took one day nap. There again, the average frequency of night waking decreased significantly, down to 1.5±1.4 per night after one month.

Bedtime fading

Time goes by, by Luca Florio | Flickr

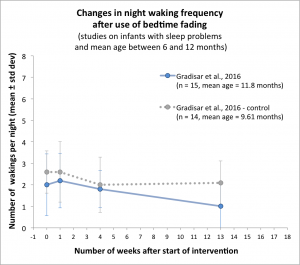

The rationale underlying the “bedtime fading” method is a fairly simple one: A baby who is not tired will not fall asleep easily. As described here, bedtime fading involves three steps:

Step 1: Find the baby’s natural sleep time. There are several ways to do this:

- Option (a): Keep a sleep diary for a few days and write down the time at which the child falls asleep every evening.

- Option (b): Put the child to bed at the usual bedtime. If the child doesn’t fall asleep within 15 minutes, the bedtime is delayed by 30 minutes the following night. If the child falls asleep in less than 15 minutes, then the bedtime is advanced by 30 min the following night. This process continued until sleep latency is consistently less than 15 minutes.

- Option (c), known as “bedtime fading with response cost”: Put the child to bed at the desired bedtime. If the child doesn’t fall asleep within 15 minutes, remove the child from the crib and allow him or her to stay awake for 30-60 minutes and play quietly. Then try again to put the child to bed. If the child still won’t fall asleep within 15 minutes, repeat the procedure, and so on until the child falls asleep rapidly.

Step 2: For a few days, the parents put the baby to bed at his or her natural sleep time, and establish a consistent, positive bedtime ritual, started 20 minutes before bedtime. The idea is that the baby will progressively associate the ritual with sleep onset.

Step 3: Each evening, parents start the bedtime ritual and put the baby to bed 15 minutes earlier that the night before, until the target bedtime is reached.

The method focuses on bedtime and does not prescribe a specific action upon night awakenings. One can thus wonder whether using bedtime fading would also, by an opportune side effect, reduce the number of night awakenings.

In the randomized controlled trial carried out by Michael Gradisar and his collaborators (described above), 15 infants, aged 11.8 months on average, were sleep-trained using step 1b of bedtime fading. This group was compared to a group using graduated extinction (n=14 infants) and to a control group without a sleep training method (n=14 infants). Both bedtime fading and graduated extinction were more successful than control in reducing sleep onset latency. However, after one month, the number of night wakings in the bedtime fading group had barely changed, from 2.0±1.4 wakings per night to 1.8±0.86 per night. By comparison, the number of night wakings in the graduated extinction group, which had started at 2.8±1.3, was down to to 1.39±1.2 after one month. In the control group, the variation went from 2.6±1.0 to 2.0±1.28 after one month. Graduated extinction therefore seemed to be more efficient than bedtime fading in reducing the number night wakings, perhaps because bedtime fading focuses on bedtime only. However, as mentioned above, this conclusion is based on a very small sample of 23 infants, as data was missing for several infants in each group after one month. Moreover, only step 1 of bedtime fading has been tested. It would have been interesting to implement the entire protocol, including steps 2 and 3 as well.

Overall, type II-graduated extinction and extinction with parental presence seem to be the two sleep training methods that combine parental acceptability, simplicity and validated efficacy in reducing the number of night wakings. More research is nonetheless generally needed for the 6-12 months age group, as I could not find a randomized controlled trial with large samples, collecting detailed measures of night awakenings and comparing all the methods (except regular extinction, which would perhaps not get ethical approval nowadays) in separate groups. This large, ideal study would however be extremely difficult to carry out, given that it puts rather high demands on a population of already overtired parents.

References

Adair, R., Zuckerman, B., Bauchner, H., Philipp, B., & Levenson, S. (1992). Reducing night waking in infancy: a primary care intervention. Pediatrics, 89(4), 585-588.

France, K. G., & Hudson, S. M. (1990). Behavior management of infant sleep disturbance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 23(1), 91-98.

Galland, B. C., & Mitchell, E. A. (2010). Helping children sleep. Archives of disease in childhood, 95(10), 850-853.

Gradisar, M., Jackson, K., Spurrier, N. J., Gibson, J., Whitham, J., Williams, A. S., … & Kennaway, D. J. (2016). Behavioral Interventions for Infant Sleep Problems: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pediatrics, 137(6).

Hiscock, H., & Wake, M. (2002). Randomised controlled trial of behavioural infant sleep intervention to improve infant sleep and maternal mood. British Medical Journal, 324(7345), 1062-1065.

Hiscock, H., Bayer, J., Gold, L., Hampton, A., Ukoumunne, O. C., & Wake, M. (2007). Improving infant sleep and maternal mental health: a cluster randomised trial. Arch Dis Child, 92, 952-958.

Lawton, C., France, K. G., & Blampied, N. M. (1991). Treatment of infant sleep disturbance by graduated extinction. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 13(1), 39-56.

Leeson, R., Barbour, J., Romaniuk, D., & Warr, R. (1994). Management of infant sleep problems in a residential unit. Child: care, health and development, 20(2), 89-100.

Skuladottir, A., & Thome, M. (2003). Changes in infant sleep problems after a family-centered intervention. Pediatric nursing, 29(5), 375.

Skuladottir, A., Thome, M., & Ramel, A. (2005). Improving day and night sleep problems in infants by changing day time sleep rhythm: a single group before and after study. International journal of nursing studies, 42(8), 843-850.